Can you tell us about your family’s Hmong American story, and what it was like to grow up Hmong in the Twin Cities in Minnesota?

My grandma and grandpa arrived in the United States first, in 1976. The church they attended, First Covenant Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, sponsored my mom over in 1980. My dad and stepmom followed through connections from my dad’s work as a pilot. I consider Minnesota my home and for most of my family, Minnesota is home to them too. This is where all our family and friends are.

I was born and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, which is very diverse. Let’s just say it was a bit of a culture shock for me when my siblings moved us to the suburbs when I was in third grade. I went from a diverse school to being the only Hmong student in a class full of white students. There was one black girl who automatically became one of my best friends in elementary school. The suburbs was only where we slept because we spent most of our time helping my sister at her shop in St. Paul. But no matter how long I live in the suburbs, St. Paul is definitely more home to me. It’s where I can find others who look like me and where I feel welcomed. The suburbs have evolved over time. As a child, my mom never allowed us to play outdoors because our neighbors would always question what we do and sometimes even call the cops on us. Now they actually come and introduce themselves and get to know who we are both as individuals and as part of the Hmong community.

How has your relationship with your Hmong identity changed or stayed the same over the years?

My business is called Maivab Photography; in Hmong, maivab means “baby.” Maivab is my middle name, something I never appreciated until I got older and touched base with my roots as a Hmong person. I originally hated the name because it just emphasized that I am the baby of my family, but as I got older, I realized how lucky I am to be born Hmong and have both an American and Hmong identity. It really opened my eyes when I went with my mom to Thailand and Laos, to see the country she was born in and grew up in. I started realizing my privilege when I saw that the country was still very traditional and patriarchal. I learned how to not take my homeland (America) for granted and also thank my parents for giving me the opportunity to be raised in America where I have the freedom and the independence to make my own choices. Until then, I never realized how much I would want to reach back to my roots to create a connection with my parents and learn to appreciate all that they went through to provide me with what I have now.

As a child, I wanted to be East Asian: Korean, Chinese, or Japanese. But that was only because I had gotten tired of explaining who the Hmong people were and where we are from. I was a little kid with only as much knowledge as what my family told me: you’re Hmong and we came from Laos and Thailand. The most dramatic event I can remember was when my teacher told me I was Chinese. I argued that I am Hmong, not Chinese. I didn’t even know how to speak Chinese. This ended with a parent-teacher conference where my sisters had to explain to my teacher that I am indeed Hmong. My sister also came in and educated the class about the Hmong people.

Those conversations are very fun and interesting now. As I got older, I started to enjoy talking about the Hmong people and my identity. There is a large Hmong population here in the Twin Cities now, and so I don’t get that question very often anymore. It’s only when I travel out of state or outside the U.S. that I get asked the question of what my ethnicity is. What I once dreaded talking about, now I enjoy. My perspective on my ethnicity and culture has changed as I've learned to appreciate my family's journey here and the rich experiences they had to go through in order to get where they are now.

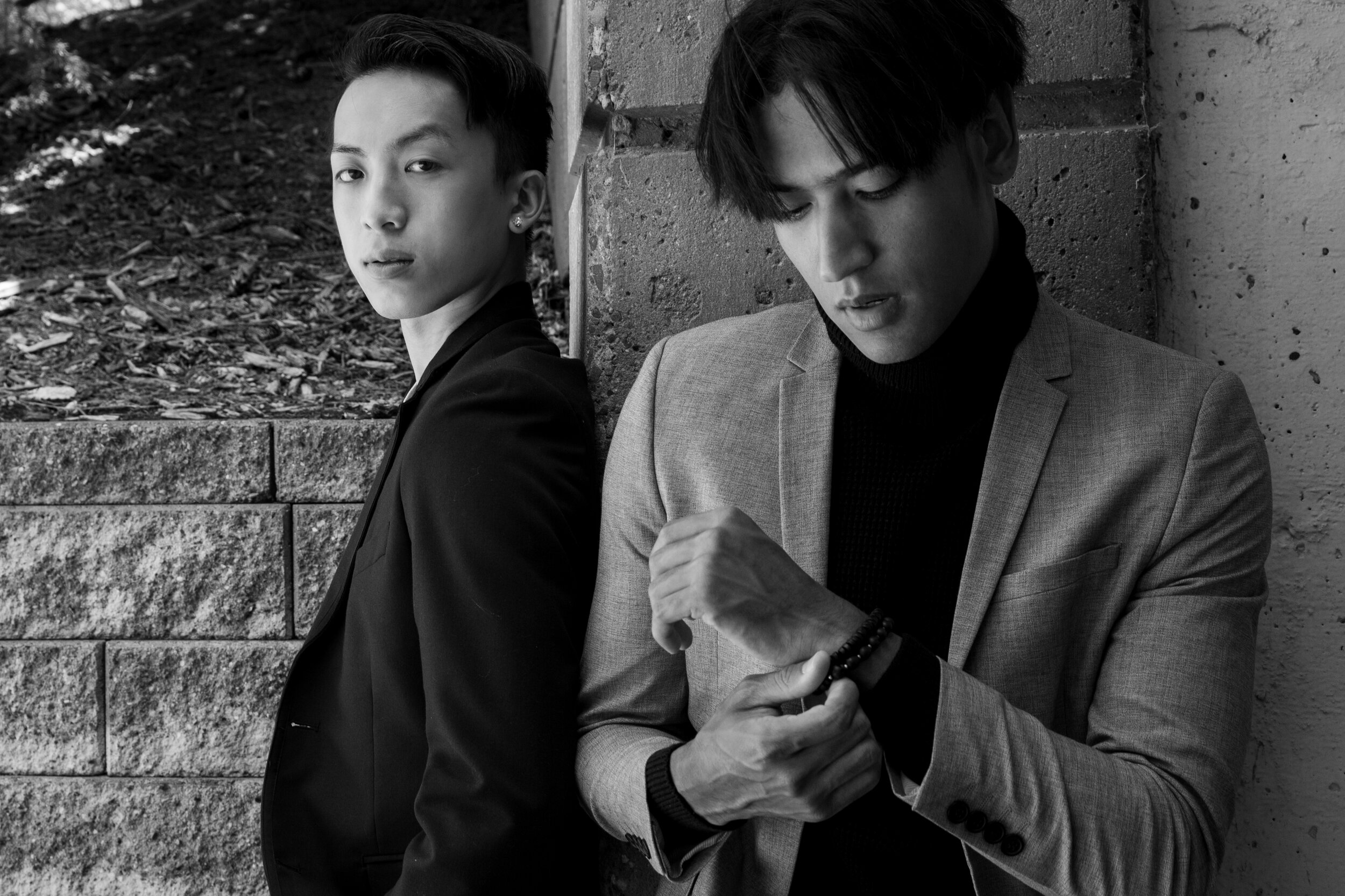

Maivab Photography grew out of a desire to use your portrait art background to showcase faces not often featured in mainstream Asian or Western media, and in particular to celebrate the beauty and diversity in the Hmong community. How and why did you start Maivab Photography? What are some of the things you take into consideration when contemplating elements like art direction, lighting, styling?

I was looking through fashion editorials and realized how infrequently Asians were being properly represented. I also noticed how my nieces were starting to compare themselves to the Westernized stereotypes of Asian beauty. I knew so many beautiful Asian people, and I wanted to start changing what is already out there. This didn’t happen overnight, though, since my skills were still at a beginner level and no one trusted me to photograph them. This led me to work on myself first. Practicing my art form on myself helped me learn how to work by myself and express myself fully without any restrictions.

After doing self-portraits for a few years, I decided it was time to start working with other people, since some of the ideas I had would be hard to do alone. My portraits were very different from the typical portraits, so I always felt out of place. But thankfully, the things that made my work different was actually the reason why other people wanted to work with me. My goal during every shoot is to make things seem effortless, and allow the model to have fun. I want this to be a therapeutic process for both my model and me.

*All photos are courtesy of Katherina Vang and should not be reproduced without permission.

For my photoshoots with models, we usually have a common theme that we focus on, like certain items I want to work around (cellophane was something I was kind of obsessed with during the summer) or a certain outfit that I want to showcase. When I’m in my zone, I get to do my creative angles and control lighting through my camera. I like to be different or try different things because everyone can do the standard, common style already. For my self-portraits, I’m a bit more dramatic because I know I can do whatever I want. They’re usually based on the mood I’m feeling or new clothing and accessories. I often don’t have anything planned, and this is how I make it therapeutic for myself.

*All photos are courtesy of Katherina Vang and should not be reproduced without permission.

Hmong artistry is a huge part of Hmong tradition, from Story Cloths to Hmong textile art. What is it like to continue this legacy in the diaspora? What led you to begin curating Hmong film festivals like Qhia Dab Neeg (the only Hmong film festival in the world), and Hmong art exhibits like the Qhia Dab Neeg Exhibit and the Hmoob Hmong Duo Sister Exhibit?

I’ve become more passionate about continuing the legacy of Hmong artistry since I realized so many of the younger generation currently have no interest in it. When I was younger, I didn’t care for it as much either, so I understand why the kids aren’t invested in this yet. But as I got older, I started wondering why we are only known for the war when we are so much more than the war itself. I think the older community continues to struggle with unresolved trauma from the war and never got the support or resources to heal; it makes sense that they focus a lot on this painful experience. I think the younger generation would like to uplift our successes, like through the Qhia Dab Neeg Exhibit and the Hmoob Hmong Duo Sister Exhibit, Hmong Arts and Crafts, and even pop-ups. There are also diverse organizations here focused on helping the Asian communities grow and evolve together. I am very lucky that Minnesota provides spaces to share cultural experiences to everyone who’s interested in getting to know our rich history.

I am proud to say I’ve helped the Qhia Dab Neeg Art Exhibit grow so much since I first started volunteering in 2015. The art exhibit is part of the Qhia Dab Neeg Film Festival created by Kao Choua Vue to specifically showcase Hmong films to the community, free of charge. I had the amazing opportunity to be the Art Exhibit Curator for four years, and eventually one of the festival coordinators for one year.

You are the founder of C.AIM Magazine, an artzine “For Artists of Color by Artists of Color,” starting with those in the Minnesota Metropolitan Area. You also work for In Progress, a nonprofit based in Saint Paul that cultivates digital storytellers of all ages and backgrounds. Minnesota is known for its vibrant immigrant and refugee communities, and it is home to the highest number of refugees per capita nationwide; however, this has also led to Minnesota becoming a target of xenophobic rhetoric. What does being able to spotlight and celebrate your local artists, your hometown, mean to you, especially given the political climate?

I feel like any state or country that takes in refugees and actually supports them will always face backlash. Mostly because change scares people, especially change they can’t control. As long as we are all in this together, supporting one another and pushing each other to grow as a community, those who put us down don’t really mean that much to me. Their words and actions hurt, but instead of wallowing in fear, we face them and it makes us stronger. That’s how our parents had to learn to survive and look how far they got. Now it’s our turn to take the lead and help build a better structure for our future generations. Being able to look up to someone who actually looks like you is incredible and so motivating. It’s harder to imagine being more when you don’t have that example in front of you. It’s moving to see someone from your community out there making changes, and I’d like us to continue inspiring our future generations to become the best they can and take up those roles themselves.

I consider myself super lucky that my art teachers supported me so much. They connected me to resources and pushed me to submit my work and even attended events where my work was being exhibited. Still, even after I had attended all these events, I felt out of place. I felt like I was that 1% of diversity in every exhibit that I was part of, like they just needed someone who wasn’t white so they couldn’t be considered racist. This experience made me determined to diversify exhibitions. I got to begin working on this goal when I began at In Progress, were I took up the role of Exhibit Curator and volunteered for Qhia Dab Neeg. I’ve always loved finding artists and promoting them. It’s been a passion of mine since I was young, so this opportunity was perfect. The first year was learning from my mistakes, the second year was building the list of artists, and the third year became smoother as I improved as a curator. The fourth year became such a big success that I decided I was finally ready to create C.AIM Magazine, something I’ve been dreaming of since I was in high school.

Taking my personal experiences as an artist and giving that love, appreciation, and support to other artists is what created this magazine. I just want to push artists out there as much as the Asian community pushes their young people to become doctors and lawyers. It’s been an amazing ride -- my team has been doing an incredible job at handling whatever I throw at them. The most rewarding part of this whole project is having artists get so excited because this is focused on helping them and acknowledging them as artists. We don’t need to have this longing to be full time artists, because we know we will create, as artists, regardless of our day jobs. But to be acknowledged and recognized for the hard work we do, that not everyone can do, it just makes our day.

Besides your passion for art, you also care deeply about mental health, a topic that still carries a great deal of stigma in Southeast Asian communities. Can you tell us how creating art has helped you manage your depression and anxiety? Are there any local mental health advocacy organizations you would recommend?

My anxiety began in school with test taking; I just never recognized it as anxiety back then. I also had major social anxiety that led me to become a hermit. I would rather stay at home in the comfort of my room than be out and about at events. Even home gatherings sucked the energy out of me, and I usually had to mentally prepare myself days ahead.

Depression set in after two of my friends committed suicide in high school. It followed me to college where I dropped out after my first semester because I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere, and that I was not good enough for anything. I started to feel nothing -- I had no motivation, no nothing. I literally just felt lost and alone even though I was with people all the time. But at that moment, I didn’t recognize it as depression. It was the people who were around me constantly who noticed the difference in my personality, who questioned how I was doing and feeling. Eventually I had to be put on medication, but my doctor recommended that I try to stay active with things I enjoyed instead of relying solely on medication. I reached out to my art teachers and they came through with resources. I dabbled in everything that had given me life in high school. These activities, like embroidery or knitting, kept my hands active and my mind focused, which calmed my anxiety, and I started falling in love with creating something out of nothing. So I always recommend art therapy to anyone who asks me what I did to help calm my anxiety.

When I first recognized I had depression and anxiety, I never reached out to a mental health professional or organization for help because I was too scared. This isn’t too surprising, since it’s not considered “normal” for Hmong families to go to therapy and seek help. I wish I was brave enough to ask for professional help earlier, but because of my fear of judgement, I held back. I was able to fight against my demons with the help of my friends and family, who helped me pick myself back up. But I do recommend to anyone who’s struggling to seek a therapist.

For local resources, one of my friends who also struggles with mental health recommended Neighborhood House in St. Paul. They provide free services for those who don’t have health insurance. I think a huge barrier for those who struggle with mental health is the fact that we don’t all have access to health care, in addition to the stigma behind mental illness. If mental health and mental illness were more commonly talked about, I think we would all be in a better place.

If folks are interested in learning more about you and your work, where can they find you?

Maivab Photography:

Website: https://www.maivabphotography.com/

IG: @maivabphotography

C.AIM Magazine

Website: www.caimmagazine.com

IG: @caim.magazine

All photos are courtesy of Katherina Vang and should not be reproduced without permission.