40 Years in Canada: From Vietnamese Boat Person to Canadian Citizen

The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 did not bring about the peace and prosperity many had hoped for; rather, tragedy continued to strike the people of former South-Vietnam as over 2 million residents risked their lives in hopes of escaping the Communist regime in their country between 1975–1995. Of the approximate 2 million escaping refugees, commonly referred to as the “Vietnamese boat people”, only approximately 800,000 survived — my father, Le Van Nguyen, is one of those people.

More than half of the 2 million refugees escaping Vietnam perished from storms, starvation, disease, and/or at the hands of pirates. (History Learning Site)

Upon sitting down with Le, he was able to divulge the details of his escape from Vietnam — including how he attained the boat, who he was with, how they survived, and ultimately, how he achieved the success he has today.

“I thought I was going to die”, 61-year old Nguyen explained, as he was describing his dangerous journey in 1979.

After the end of the Vietnam war in 1975, the Communist government of Vietnam imprisoned all former military officers and government supporters of South-Vietnam into prison camps, officially called “re-education camps”. In one of these camps, was Le’s older brother, a former military officer. At the time, the eldest brother of the family, Yen, was pursuing a PhD at the University of Toronto and was able to send $2000 back home to his family in hopes of being able to make an under-the-table deal to release his imprisoned brother. After a deal was unable to be made with the jail guards, Le took this money and decided the best course of action was for him and three of his other brothers to follow suit with many other former South-Vietnam residents and escape the country.

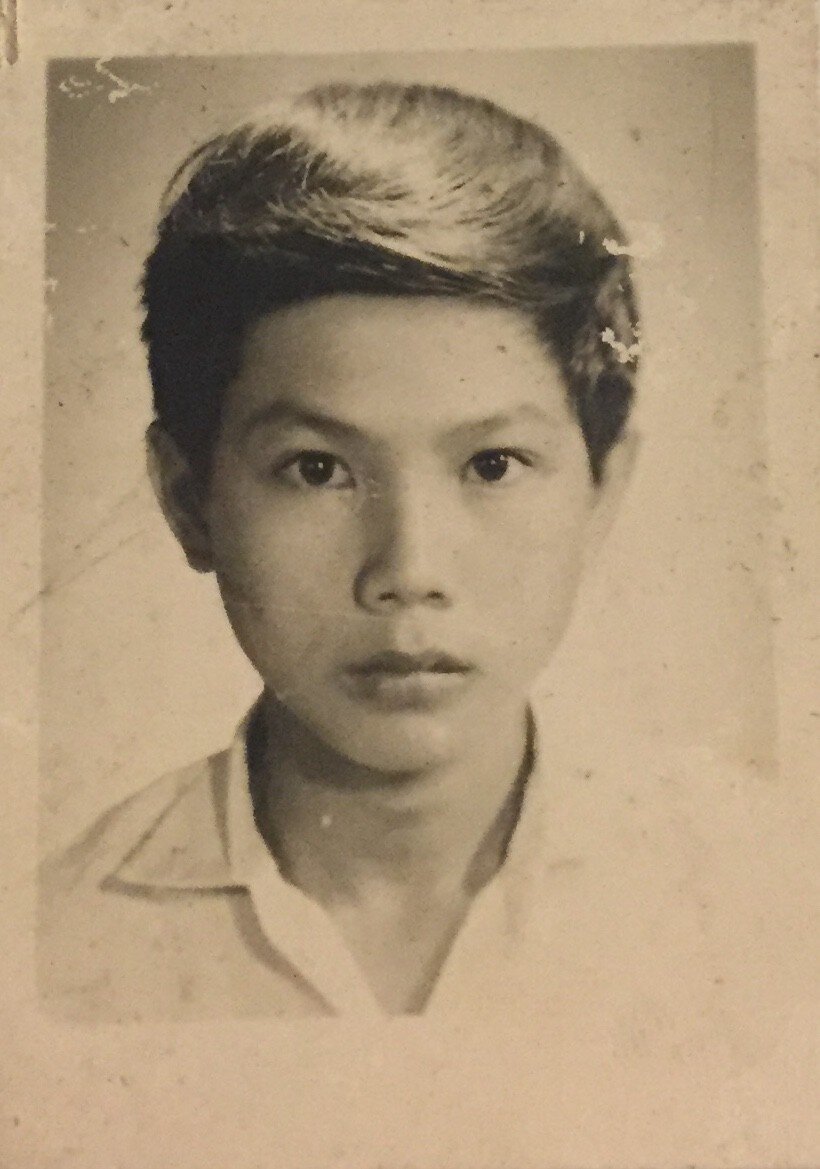

School portrait of 14-year-old Le Van Nguyen in Vietnam. (Le Van Nguyen)

Le (far left) and friends in his hometown of Nha Trang in 1975. (Le Van Nguyen)

Upon befriending a man in a small fishing village, Le and his brothers were able to secure four spots on a small fishing boat leaving from Cam Ranh Bay with the money their eldest brother had sent from Toronto.

“After 6 days, we ran out of oil and the boat just floated.”

Without a captain or anyone with sailing experience, the small fishing boat took off with twenty-two onboard, including one woman and two children under the age of 5. The group carried with it one small drum of water and what food they could carry. On the very first day of travel, the group was hit by a massive storm. “The drum of water cracked. We lost all the water,” Le explained. The storm also destroyed most of their food supply. “Some days, we catch fish. Some days, there is heavy rain and we catch water.” The only source of food was the fish they caught by hand and ate alive, and the rain water they were able to collect in canisters. Following the rise of the sun, the group continued East. “After six days, we ran out of oil and the boat just floated.” The fishing boat floated for another sixteen days before being rescued, totalling twenty-two days on the open ocean.

“Everyday, people cried and we prayed a lot.” Le claims that no one on their boat believed they would survive. “Two men were so nervous that they lost control and jumped into the ocean. They thought they could swim to shore. No one has ever seen them again.”

After twenty-two days of floating on the open ocean, praying to be saved, they were finally spotted by a Filipino transport ship, shipping rice from Manila to Tara Island.

“Nobody wanted to help us. They didn’t want the responsibility.”

Le claims that many large ships had passed their small struggling fishing boat before one finally looped around to pick them up. “The captain was a good catholic man.” The Filipino crew pulled the boats together and pulled the surviving twenty refugees to safety.

A small fishing boat awaiting rescue by the USS Blue Ridge (Defence Imagery)

“The captain made us some milk and gave everyone a little cup and some crackers.” To this day, Le still claims that this is the best meal he has ever eaten.

Upon arriving on Tara Island with the transport ship, they were immediately given medical treatment, more food, and clothes. After spending several days on the island, a filipino navy ship had arrived to bring the group back to Manila, as per requested by the transport ship captain. Immediately following their arrival, Le and his brothers rushed to the Canadian embassy as soon as they were able. The eldest brother, Yen, who was completing his PhD in Toronto, had sent over an application form for immigration sponsorship before the brothers had made the dangerous journey on water. Le had travelled with these important documents sealed inside of a plastic bag and sewn into his jacket. “I go directly to the Canadian embassy in Manila and tell them I have a brother. Here is the paper. Please help me.”

“We got very lucky because we got a short cut. We lived [in the refugee camp in Manila] for one week before they transferred us to another island, where we lived for a few months”. The four brothers were approved for sponsorship in a matter of three months, a feat that is nearly unheard of. “Most of [the refugees] live there for more than a year.”

The Nguyen brothers had finally made it. They landed in Edmonton, Alberta in late-1979, where they stayed at an army camp for several days before flying to meet their eldest brother, Yen, in Toronto. Yen took them to his apartment, showed them how to navigate the Toronto subway system, and brought them to a Canadian Welcome House, where they were given an OHIP and were helped in their job search.

“Two brothers worked as carpenters in one division, and the other two worked as carpenters in another.” Each making $3.50/hour, the four brothers were able to rent a two-bedroom apartment between them. “We worked for only 10 months. We saved about $3000, after we paid for food and rent.” With this saved money, the brothers were able to all put themselves through school.

Le points out how he never made withdrawals from his account, only deposits. He claims this bank book marks the moment he realized he could go back to school. (Jaime Nguyen)

Prior to fleeing the country, Le had been studying animal biology. He had no transcripts, and therefore had to start over. He chose to pursue a diploma in boiler room engineering at George Brown College in Toronto. “It was very easy for me. I had good basic knowledge. The only problem was English. I can read it, but when I talk, the pronunciation is not 100%. I learned English back home, but we never spoke it.”

Le was to able further his English speaking ability by watching films, reading books, and writing down new words. Above is his 1981 English notebook. (Jaime Nguyen)

Despite the language barrier, Le was able to continue his studies towards his diploma, in addition to learning English, and graduated with his class and became a certified stationary engineer in 1986.

Le proudly displays his first certification. (Jaime Nguyen)

Immediately upon graduation, Le was able to gain employment. “My first job was at the Canadian Linen Supply, looking after the boiler in 1982,” where he remained for 5 years. His next position was with Tencorr Packaging Inc., a paper manufacturer, where he worked as a technical engineer for many years, before being promoted to supervisor, where he remains today, totalling 30 years with the same company.

Le has been working for Tencorr Packaging Inc. for nearly 30 years. (Jaime Nguyen)

The resettlement of a Vietnamese boat person is one that is a difficult and long process, however, it is evident that given the story of Le Van Nguyen and many other alike, it was one that was well worth the risk. The choices that were made decades ago certainly resonate with today’s generation.

Hanh Ngo is a 20-year-old London resident whose parents made the dangerous journey escaping from Vietnam in 1982. Her father, Long Ngo, is a childhood friend of Le Van Nguyen. “My dad was one of the organizers of numerous boats trying to leave Saigon (now modern day Ho Chi Minh City).” With a wife and two-year-old daughter (Hanh’s eldest sister), it took Long nearly two years to plan his own journey.

As the youngest of six children, Hanh believes that she had the smoothest of upbringings compared to her siblings. “As my older siblings were growing up, my parents had a lot of financial issues.” As is the case for many escaping from Vietnam, the Ngo family came to Canada with nothing but what they had on their backs. After years of doing odd jobs to pay the bills, Hanh’s father finally opened up his own Vietnamese restaurant in London, Ontario.

“My parents’ journey and struggle from Vietnam to Canada has definitely influenced me and the person I am today”.

Despite working 12-hour days everyday, Hanh claims that her parents are still the happiest and most loving people she knows. “They have taught me that things don’t come easy in life and if I want something, I have to work hard to get it.”

The Ngo family proudly hangs this London Free Press article written about their success story in their London family restaurant. (Hanh Ngo)

Stories like those of Le Van Nguyen and Long Ngo are testaments to the age-old “Canadian Dream”.

Success is subjective; it is something that is different for everyone. For Le, he’s achieved as much success as he could have ever dreamed. “I got the house. I got the car. I got my children. Both of them in University. I’m so happy.”

When asked what the proudest moment of his life is thus far, Le responded without hesitation: “I am proud to be a Canadian, a Vietnamese-Canadian.”

Republished with permission from Jaime Nguyen. Click here to see the original piece on Medium.