Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

My name is Pajouablai Monica Lee, and I am Hmong American. I am originally from St. Paul, Minnesota, and come from a big family as the middle of five children. After going to public school in St. Paul for all my life, I went to the University of Minnesota for my undergraduate degree in Human Resource Development and went to work for OCA - Asian Pacific American Advocates in Washington, D.C., after graduation.

Where is your family from? When and how did they arrive in the United States?

My parents are originally from Laos, a small country in Southeast Asia that is sandwiched between countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia. My family, like many other Hmong families, were victims of the Secret War in Laos. After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, my parents and their families fled to Thailand where they stayed in refugee camps for nearly 10 years. My dad’s family arrived in the United States first on June 24, 1984, and my mom’s family came afterward in December 5, 1985.

My parents met in the refugee camp in Thailand. My mom was a literature teacher, and the story goes that my dad saw her one day and wrote her a letter, beginning their courtship. My dad’s family settled in St. Paul through my uncle, who had been sponsored over earlier by a few kind missionaries, but because my dad left the camp first, my parents had to maintain a long-distance relationship. My mom’s family originally was sponsored to Spokane, Washington, before moving to Wisconsin, ultimately settling in the city of Wausau. Then my mom moved to Minnesota after her and my dad got married, while my mom’s family remained in Wausau, WI. My dad wanted to be closer to his family and [likely] because Minnesota has the largest Hmong population in any metropolitan city in the U.S.

I [regrettably] don’t actually know too much more about my family’s story because they don’t really talk about this time of their lives, but it is also partly on me and my siblings and our lack of due diligence in asking about these things. What I have learned is usually pieced together from conversations that arise when my parents are triggered in some way or feeling nostalgic.

What was it like growing up Hmong American in St. Paul, Minnesota?

Minnesota is home to a huge Southeast Asian American population and is also a sanctuary for many other refugee communities. I think growing up in a predominately Hmong community was unique because I did not feel particularly Othered in ways other Asian Americans might have. The Hmong here are somewhat majority-minority and so I was always surrounded by other Hmong folks, and it was not until I was a lot older that I became more aware of my race or even saw myself as an Asian American — to me, I had always identified as Hmong American. The Midwest definitely has a majority White population, but we also have these really tight-knit ethnic communities, and being a part of the Hmong community in St. Paul really helped build my self-confidence and develop a deep sense of appreciation for being Hmong.

For example, we have the Hmong Farmers Market, Hmongtown Marketplace and Hmong Village, the Hmong New Year Festival, the Hmong soccer tournaments — those were my favorite places and some of the go-to-places for a lot of Hmong kids while I was growing up, especially since we didn’t have cars or our parents did not always trust us to go to other places like birthday parties or sleepovers. So we would go to these big Hmong gatherings where many Hmong people would show up and you were able to hang out with your friends. You get to plan to meet up in your Hmong clothes or in matching outfits, as well as meet and find other boys and girls to play ball-toss with or just to talk to. I never realized how much going to all these events meant to me until I was older. I remember how my mom, who was very entrepreneurial, had this garden and she would sell her crops at flea markets like so many other Hmong folks do, and later she took up selling merchandise as well. I would always be very excited to go with my mom and help her sell her goods, and get the chance to see the other Hmong vendors and their stalls. I think moments like these really helped formulate my Hmongness, my identity as a Hmong child of refugees and as a Hmong American.

Unfortunately, there were also a lot of moments where I felt ashamed to be Hmong, but did not really know how to process it at the time; sometimes it’s not until I look back that I realize something was problematic. For example, gang involvement is a huge stigma surrounding Hmong men and Southeast Asian communities in general, as well as other communities of color that have darker skin tones or come from lower-income families. So having grown up in these communities and seeing the effects of this stigma and stereotype, I did have times when I wondered things like, “Is it bad to be Hmong?” There was another time when I was in middle school and I definitely had a different vernacular then — my speech was more casual, informal, and more “street,” and a lot of it was because of the people and friends I was with, many of whom were Hmong kids who grew up in this almost gang-like culture. One of the things that affected me was when people commented on how I spoke. My older sister would say things to me like, “You’re so ghetto,” yet when I was with my friends at school and in advanced classes, some of my Hmong friends would say, “Oh Monica, you speak so white, you’re so whitewashed.” I remember it being a difficult time for me because these concerns of how I wanted to present myself affected how I carried myself throughout school and later into my career. I started letting these thoughts get to me, which created this layer of insecurity and anxiety. I don’t blame anybody though because in fact, I think a lot of these comments probably were rooted in deeper things that each of these folks were going through. I think my sister said “Oh, you sound so ghetto” to me because she wanted me to be perceived as someone successful or as someone who could speak “proper” English. On the flip side, I think my friends said those things maybe because it was confusing why we had such different educational trajectories and experiences.

As for a moment when I was most proud to be Hmong, last year I gave a fundraising pitch at OCA’s annual Corporate Achievement Awards where we honor our corporate partners for their support. I started as an intern at OCA and I wanted to highlight the importance of our internship program and how it helped uplift young leaders such as myself and many others who went through the program. I was able to tell my story and my parents’ story and talk about my trajectory and journey of how I got to D.C. and into the program. Ultimately, I was able to raise $44,000 dollars during that single awards dinner. I think that was my proudest moment to date because I never really understood the power of my story until then, and never realized how lucky I am to be able to do work that connects my personal and professional passions. It’s been rewarding for me, especially as a Hmong person and Hmong woman, because the statistics are against us, the decks are stacked against us, yet somehow I managed to make it — I’m not supposed to be here, but I am because of programs like OCA, and of course, because of my parents' unyielding support and influence. Being able to use my voice and raise this incredible amount of money means so much to me, because now I can directly impact someone else’s life the way OCA impacted mine.

Monica giving remarks during the OCA Convention workshop she planned.

For our video campaign about being a #ChildofRefugees, we asked: “What do you wish your teachers knew about your Southeast Asian American experience?” You submitted the following response: “I wish my teachers knew that The Secret War was different from the Vietnam War. And our parents and elders are scarred and never want to look back. So we grow up and go to school not even questioning the history lessons because we don’t know the full histories ourselves. But I also wish my teachers knew how grateful I am for them calling me by my name(s) and letting me and Hmong friends speak Hmong in class & eat our Hmong lunches in our classes so we got to be ourselves and eat what was ‘normal’ to us. Thank you.” Can you talk a little bit more about your own experience learning about Hmong history and culture and your broader educational journey as a Hmong American?

As I was writing my response, I immediately thought back to my high school experience in World History and U.S. History classes, and how everything I learned was very surface level. Everyone knows of the Vietnam War because America was directly and visibly involved, but no one knew about the Secret War because, well, it was a secret war! I did not even really learn about the Secret War until I was in college and post-college, and I’m still learning about it today. As I mentioned earlier, my parents don’t really talk about it and I don’t ask my parents enough about it.

I don’t give enough credit to my parents, but I honestly do also get a lot of information from them. My dad is one of those silent scholars who collects books and newspapers related to Hmong people, Southeast Asians, Asian Americans —anything AAPI-related. I’m really fortunate that my dad is educated and literate and that he believes retaining any information on our community is important. And I was very fortunate to attend the University of Minnesota. While there were only a handful of Hmong faculty professors, they still had courses about Hmong culture, Hmong history, and the Hmong American identity and experience. It was the first time that I learned college courses about my community even existed. However, there needs to be more literature and research on the Hmong community because I wish that we had this history included in our general school curriculum growing up. I was lucky to go to UMN where there are Hmong-centered classes, but it is because there is such high demand due to UMN’s large population of Hmong students. It makes me wonder if other institutions are offering these types of courses, especially in areas where there is not as big of a Hmong or broader Southeast Asian presence.

Going back to my own personal experience, I was really lucky to be able to go to a magnet school where my 4th and 6th grade teachers in particular were hyper-aware and very welcoming to Hmong students and Hmong refugees, possibly because they were trained for it. My teachers were very receptive of my Hmong friends and me eating our own Hmong food inside their classrooms, and I remember how during the Hmong New Year, they would start conversations with us about what food we were having for that week and even understood what we were doing. I never realized how important these moments were at the time, but I did go back years later to visit my teachers and tell them how much of an impact they made in my life.

You are currently the Associate Director of Programs at OCA - Asian Pacific American Advocates, a non-profit based in Washington, D.C., that is dedicated to advancing the social, political, and economic well-being of Asian Pacific Americans. Can you tell us a little more about OCA, as well as about some of the projects that resonated deeply with you? And how do you as a Hmong American make sure your community’s needs and voices are reflected in the work that you do?

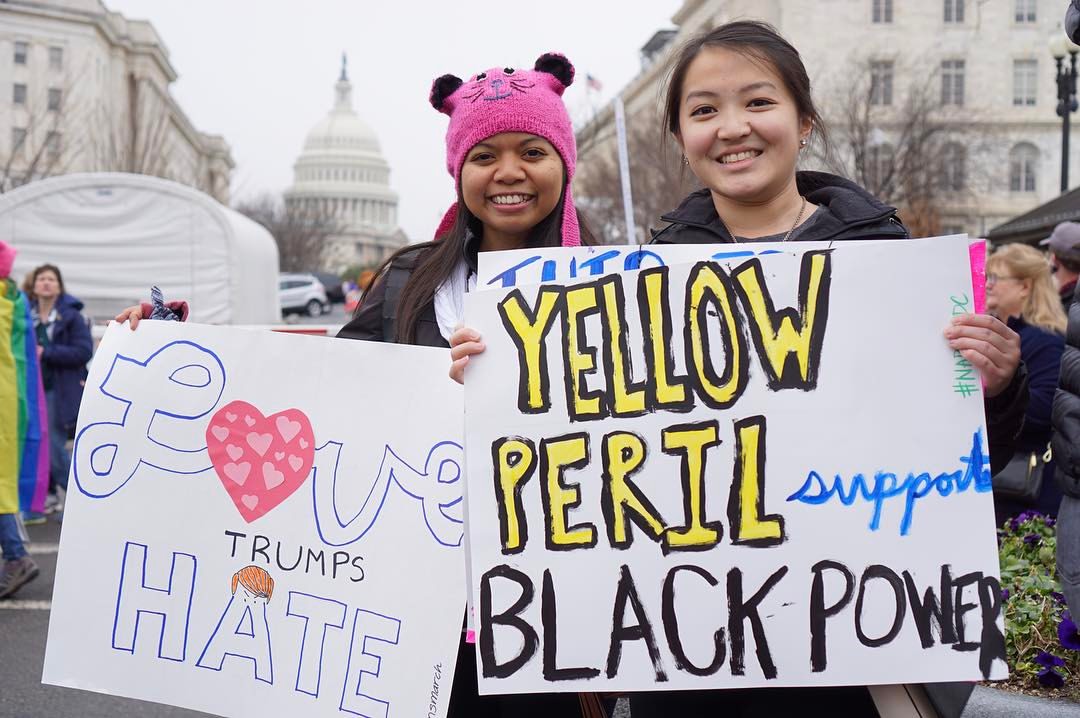

Monica with her friend Maria Manalac during the first Women’s March in Washington, DC.

I have been very fortunate to be a part of OCA for the last four years. OCA is a one of the oldest Asian American civil rights organizations, founded back in 1973 originally as the Organization of Chinese Americans. After much input and thought about the changing community around us, OCA really wanted to be more intentional, reflective, and inclusive of the broader community that it serves, so then it became more of a pan-Asian organization serving all AAPI communities. We are national non-profit, membership-driven organization and we work to advance the social, political, and economic wellbeing of AAPIs. Our headquarters are in D.C. but we have about 50 chapters and affiliates throughout the country. We try to advocate on issues like immigration, education, broadband access (tech and telecom), and basic fair treatment and civil rights for all AAPIs.

I started off as a intern and was fortunate enough to later become a Program Associate, where I began managing the Mentoring Asian American Professionals Program, the B3: Build, Breakthrough, Believe Program, and the AAPI Womxn’s Initiative. The goal of our programs is to help build a pipeline where we can prepare all AAPIs to be leaders in their fields, industries, and passions, to empower AAPIs to be who they’re meant to be and help them in the workforce, particularly through professional development. I’m particularly proud of The AAPI Womxn’s Initiative, which [I actually helped founded] back in 2016, because while it is still a small and young but growing program, it represents a step forward in OCA’s effort to be more inclusive and aware of the issues that AAPI women face. We wanted to create this platform where women could come together and talk about our challenges, to share and own our stories, and to support one another. Especially since the theme of our summits in 2018 was “Year of the Woman,” we wanted to make sure that everything we did was intentional and reflective of the landscape we live in and the multitudes of identities we want to advocate for and represent, and to make it clear that every year and every day is our time. [My coworker and I even co-authored a resolution to have OCA support and advocate on issues that affect AAPI womxn.

Fierce Advocate and friend of Monica’s, Viet Tran posing at APAICS’ Annual Gala 2018.

As a Hmong woman, I feel like a lot of the struggles and challenges I have faced might resonate with others, and so hopefully me being here in this space will provide that perspective and experience that can really push OCA to be more inclusive towards everyone we are trying to help. For example, I work really hard to have diverse classes, program participants, internships, and guest speakers. And I’m always trying to make sure my community is reflected in the work that OCA does, to bring in our stories and our voices. I do believe that my presence and my representation is so important in today’s time -- just being here, taking up space, and being an example to other Hmong and Southeast Asian kids and proving that we can be leaders everywhere if we use our voices to speak up and be heard. This is our time.

What led you to the world of advocacy in the first place, and do you have any advice for Southeast Asian Americans hoping to get involved in this work?

I have to credit my parents and my upbringing for their huge impact on the advocacy work I do now. My dad was the youngest member of his family and when his family first arrived in America, he was actually the only one who could go to school, going first to high school and then later to college in St. Paul, and ultimately a Master’s degree in Urban Planning from the University of Minnesota. My mom was and still is an educator, and she works at an elementary school as a home-school liaison helping families get registered and acquainted with the public school system. Both my parents have been public servants their entire lives, and they instilled these values in my and my siblings. They taught us about working hard and valuing education as the ladder and way out of poverty, but also about being self-sustaining and the importance of giving back to the community that helped you get there. For example, my father’s older brothers had to sacrifice their own money and their own education to help my dad get his education and degrees. After college, my dad’s first job was actually as a park ranger because he really enjoyed the outdoors. He then became a community organizer and campaigned for Congresswoman Betty McCollum, and when she was elected, my dad was hired onto her staff to handle case work regarding the Hmong community.

Monica with her mother and grandma, who she credits much of her inspiration to.

My parents led by example, serving as prime role models for my siblings and me, and it probably is not too surprising that my older siblings are currently public servants as well. My sister is currently working on the Hill in D.C., and my brother is currently trying to get his law degree. I am so grateful to have grown up in this family, and I know that I had a lot of access and privileges that not a lot of other kids had, which is why I want to make my work worthwhile and really try to pay it forward so that other students can have these opportunities. I want to try to open the door a little bit each day so that other Hmong students, who may not have had the same privileges that I did, will be able to find the resources and can see that there are Hmong people out there doing things and realize they can do this too.

Monica with her parents and sister, her first teachers and role models in life.

In terms of how folks can get into advocacy work, I think it’s important to get involved at a young age. For instance, if you are on a college campus, there are usually a number of student groups or advocacy groups that you can join and get opportunities to learn about civil rights, how to organize students and people, pass legislation, fundraise, etc. From there, folks can start following the work of organizations such as AAJC, OCA, SEARAC, NAPAWF, Hmong National Development, BPSOS and more, and find ways to apply to their internship programs or get some exposure either in D.C. or at the local level. You can even just follow blogs or hashtags such as the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the #MeToo Movement, or the Parkland students’ movement for gun control reform. In these examples, many of the folks on the ground organizing are students, and we have seen firsthand how they have significantly changed how we do politics. There is this myth or misconception that being an activist is defined by how loud you are or how often you protest in the streets, but getting involved in activism can be as simple as picking up an article, reading about the issue, and talking about it with your friends, and realizing that activists come in all forms, from the people working in non-profit spaces to the teacher in your classroom. I know that many folks have been afraid to talk about the issues because they think it’s too touchy or they don’t want to offend people or that it’s too much work and that they would rather sit back -- I would disagree. I don’t think we can ever be too political because everything we do or anything that touches us is political: the money we are making, the taxes that they're taking out of our income, the healthcare we are receiving, the education system we have, and the media we are exposed to. I believe that change happens when we acknowledge what is happening and begin having dialogues about it. I have also noticed that in many instances, when it comes to the Asian American communities, often times we only care when things directly affect us, and so I think it’s important to encourage one another to care about matters that concern people within and outside the community.

I would implore all youth today, myself, my colleagues, and friends to really reflect and think about the little things that we could be doing every day, whether that involves having an open conversation with our parents about issues that matter to us or signing a petition or submitting a public comment. I know that worry of being bothersome that comes up when we ask our family and friends to help us, but then I think to myself, this is my network -- our family, our friends, and our professional networks. These are the very people we should be going to for support, and the word of mouth or the share on Facebook can help create meaningful dialogue and help create this momentum for change. I remember when I reached out to the Hmong community for help with the campaign against Public Charge through my Facebook and personal email accounts, and they mobilized so quickly that we were able to really get awareness out on the issue.

Monica with Congressman John Lewis on the steps of the US Capitol.

And if you are a Hmong woman or Southeast Asian youth who is not sure about what you want to do with your life, don’t worry because you’re going to be fine. You’re going to do great things. Don’t let the imposter syndrome stop you from achieving the greatness that you’re meant for.

What are some amazing organizations doing advocacy work for the Hmong or Southeast Asian American community that you would like to spotlight?

I have been really fortunate to have a community everywhere I go, or at least the opportunity and ability to build community. Hmong Innovating Politics (HIP) is an awesome progressive organization that is focused on strengthening the political power of Hmong and disenfranchised communities through civil engagement and grassroots mobilization. They have two offices, one in Sacramento and the other in Fresno. I have good friends who are both community organizers and HIP board members, and they have been working really hard on voter engagement, youth leadership, peer engagement, education advocacy, overall social justice, and coalition building, understanding that our issues are tied to the Black and Latinx communities.

I also want to spotlight MAIVPAC, the first Hmong American women’s political action committee in the U.S. They started this year as an effort to organize and mobilize for Hmong candidates and to endorse candidates who they think will serve the community. This PAC includes Hmong women leaders, trailblazers, and pioneers that I stand on the shoulders of and they are the ones who paved the way so that I could do the work that I do. The Hmong community has been here for over 40 years, and because of the phenomenal work of this PAC, we have elected a record number of officials this year, and we have many Hmong folks throughout the country who are getting involved and demanding that our voices be heard.

SEARAC is another organization that is doing amazing work to uplift and empower Southeast Asian communities. I’ve had a lot of friends who work for them, including my brother. OCA has partnered with them on a number of projects regarding coalition building, immigration, and education.

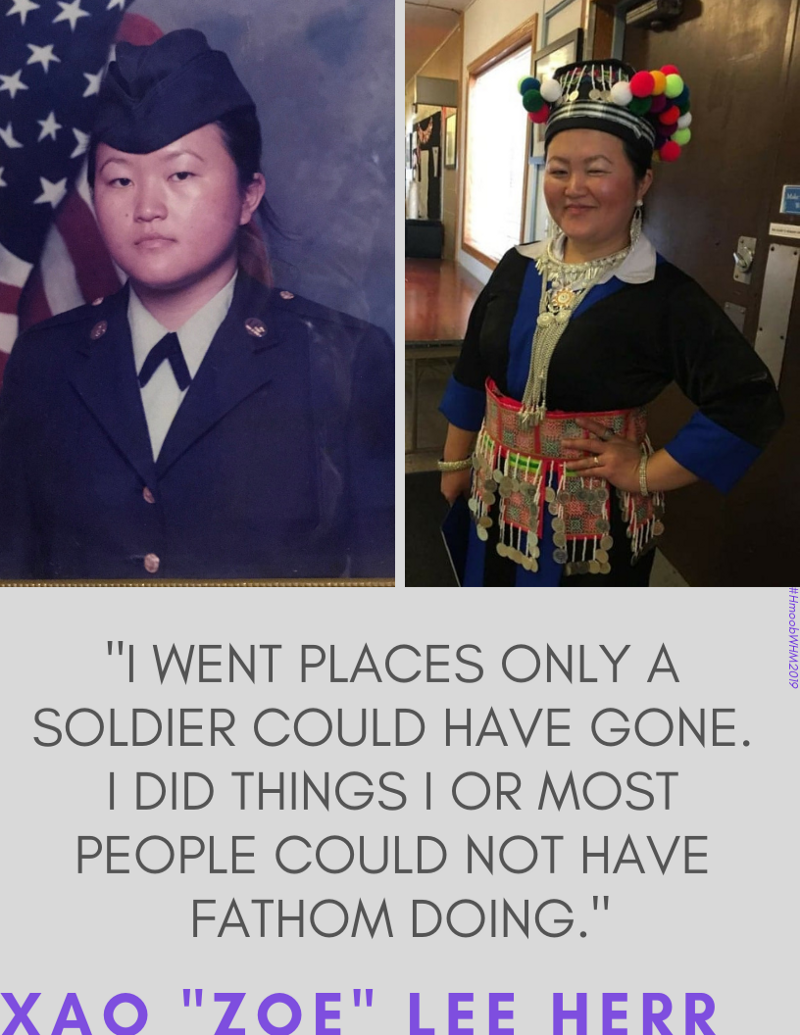

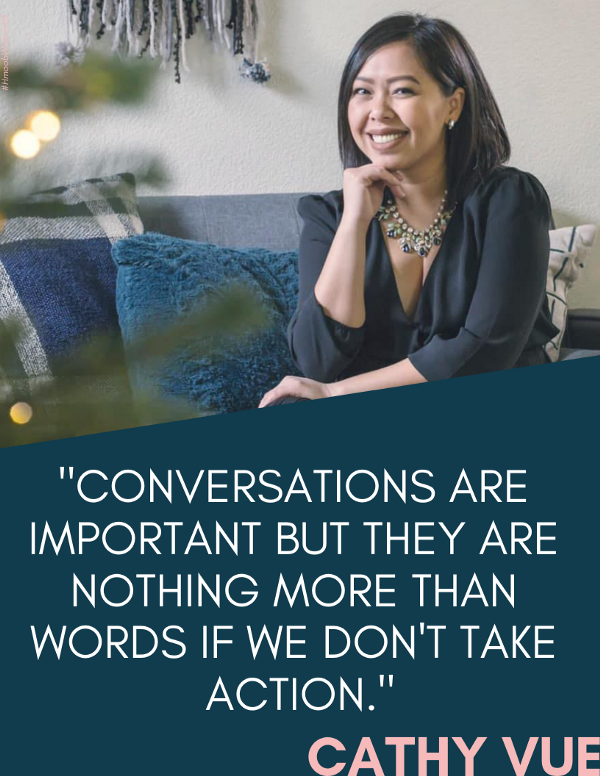

Monica also recently started a #HmoobWHM2019 Spotlights project in honor of Women’s History Month where every day she will spotlight a different Hmong womxn in her life.

I created this Medium account to capture the stories of the Hmong womxn and girls in my life, family, and extended network. Too often I noticed that my Hmong peers and family members — almost always women — were too humble, shy, or simply didn’t think they had a story worth telling. After realizing the power of my own story only a little over a year ago, I wanted to provide these women a platform to share their stories.”

In honor of this year’s Women’s History Month I’ll be spotlighting Hmong womxn from all across the country. I created a form that asked a series of questions about their lives and asked them to answer the questions that they were comfortable sharing. Their stories of strength, resilience, vulnerability, love, courage, family, sorrow, and so much more will move you, inspire you, motivate you, educate you, and simply entertain you. Join me on this journey as I aim to uplift the voices and stories of every day Hmong American womxn so that we can continue to inspire and empower one another.

Here are some of the previews from recent posts: