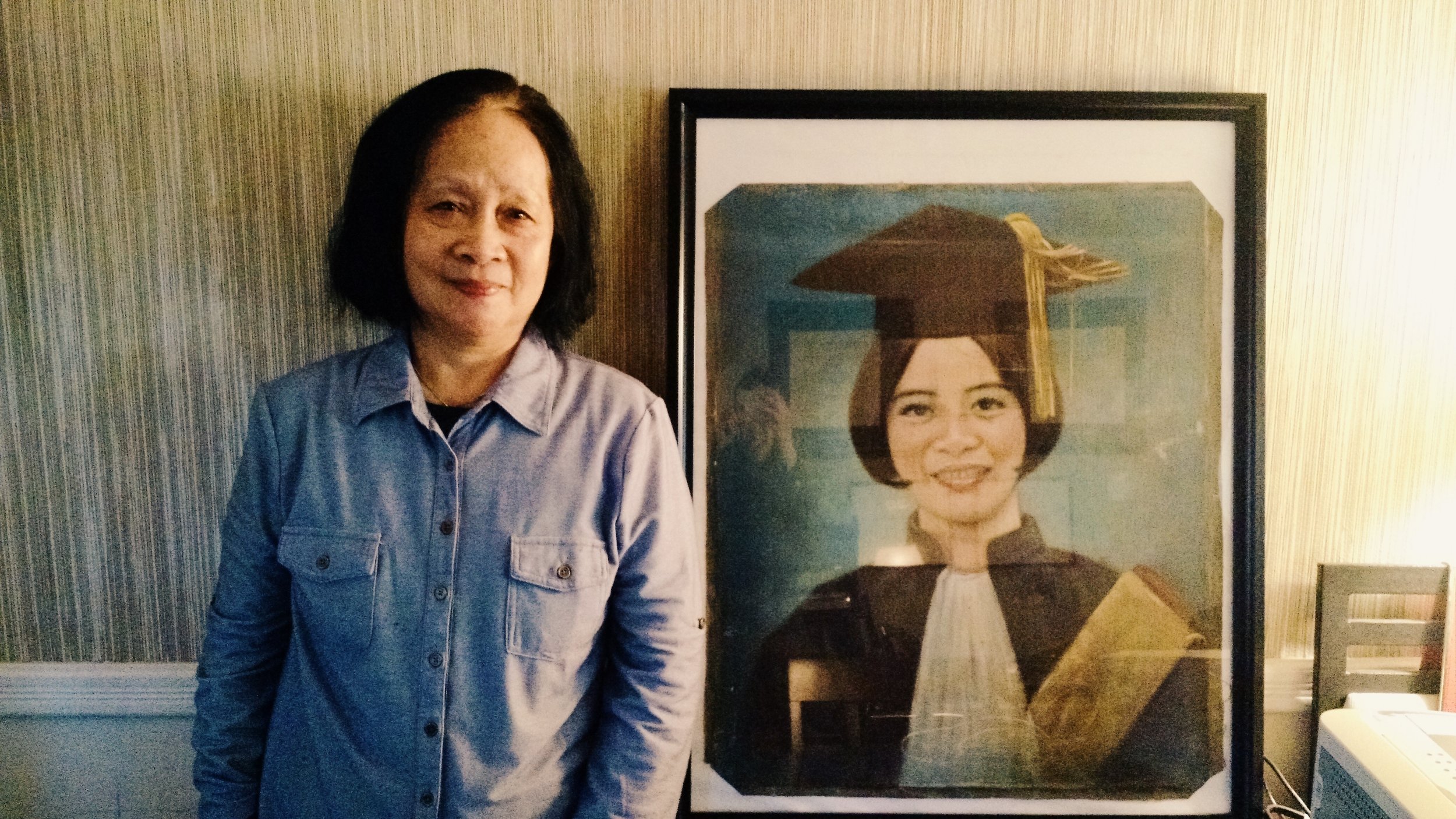

Thien Tho Ngoc Nguyen standing next to a painted portrait of herself to celebrate her graduation from Dalat University.

Would you please introduce yourself?

My name is Thien Tho Ngoc Nguyen, and I am Vietnamese. I was born in 1944 in Saigon, Vietnam, so this year I’m almost 72 years old. I came to America in 1992 when I was 48 years old, sponsored by my younger sister who came to America in 1975. My sister is unique because with her husband and his family, they escaped Vietnam on a boat. Many Vietnamese people escaped to America after the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the day the Communists took over and the day many Vietnamese people consider as the day they lost their country. After making it to America, my sister became a U.S. citizen in 1980 and was able to sponsor all our family members from Vietnam over here. Our family is very big because my parents had six boys and six girls – 12 total kids – and my younger sister sponsored six families of her brothers and sisters to the USA. Now, my family here totals about 100 people! Everyone is successful and happy, very happy.

Can you please tell us a little bit about your childhood, what it was like to grow up in Vietnam?

Everyone who lived in my area loved our country, and we were happy. When I was young, the elementary school was next to my house, and I was surrounded by friends and family. Everyone knew each other. I remember how my neighbors loved to exercise, and one morning at 2 a.m., I woke up, went over to my neighbor’s house, and knocked on the door to wake them up to begin our morning exercises. Afterward, we were wondering why even after we had exercised for so long, the sun still hadn’t come up; we then realized that it was 2 a.m., not 5 a.m.!

When I got to high school, at around age 13 or 14, my neighbors and I rode our bikes to school every day. I remember how after exercising, we would put on our Ao Dais [traditional Vietnamese garment], and because we were on our bikes, we had to tuck the back flap in so the cloth wouldn’t get caught in the bike tires, and hold onto the front flap so nothing would rip. Every day on our way to school, there would be a whole group of boys riding behind us. I don’t know who they were or how they knew our names, but they would call us out and playfully tease us. It was a happy time.

When I got to college in 1968, I moved to Dalat to study in Dalat University. Dalat was the town that was selected to open a new faculty started by Father Nguyen Van Lap, Father Nguyen Van Ly and some Vietnamese professors who had studied and worked in the United States and wanted to share what they learned with the Vietnamese students: Politics and Business Administration. I went to Dalat with my older brother and some other friends. I was part of the first course of Politics and Business Faculty in Dalat University in 1968. Even in 1975 when the Communists took over South Vietnam, the University stayed open, and graduated 16 or 17 courses. The Dean of Politics and Business Administration Faculty, Mr. Tran Long, is still alive and we meet with him every year. He is now 88 years old and he comes to the annual reunions attended by many alumni, many of whom are in the U.S. now.

I was so sad after the Communist takeover because a lot of my friends had left, as well as some of my brothers and sisters. Sometimes I wanted to commit suicide because I was so depressed, but I told myself, “How can you consider suicide? Your husband is still here, your kids are still here. My parents and several siblings are still here. Why am I sad then? Why am I crying every day?” Life had changed so dramatically after 1975. For example, before, every morning we went out to eat breakfast, and we had a servant to prepare meals for my husband and I and to take care of my children. We also ate out a lot at night, since I worked at a bank, customers would offer to treat us out all the time. We had a government car, and we had a rented home. After 1975, when my older sister and her family fled the country, my family and I moved into their home. My brother-in-law’s family was very rich, they actually left behind 5-6 houses in Vietnam.

Because I didn’t like living under Communist rule, and I couldn’t really work with them, I started going to the temple. I really enjoyed listening to sutras and learning how to meditate - to keep our minds tranquil and quiet, and to be mindful. Buddhism helped me a lot; it really changed me and helped me get out of my depression. The sutras taught me about cause and effect, and trained me to have good thoughts and to help others. The first five years after the Communist takeover, I was so depressed, and thought often about escaping the country. But after finding the temple and Buddhism, I found happiness in my mind. I began teaching the monks and nuns in the temple English, and did a lot of community service. I stopped blaming the Communists for everything, and I stopped being sad and contemplating suicide. My mindset about the Communists changed, and my heart was bigger. Now that I’m in the United States, I see so many people who really hate the Communists, who protest them, but I choose to live my own life and not let the hatred and anger take over. I realized that the monks and nuns at the temple were so compassionate and happy and young because they did not hold onto hate and anger, lived simple lives, ate what they had and wore what they had - not wanting for this and that, and ate vegetarian meals. I really like this way of life and thanks to this lifestyle, most people when they see me think that I am 50 or 60 years old; meditation has helped me to master my mind and ideas, and sitting cross-legged for so many years has helped my circulation and my overall health.

You said that you came here in 1992. Can you share with us your memories about the Fall of Saigon in 1975?

I remember everything very clearly. No one who lived in Vietnam can forget our identity or our homeland – it was so hard to leave. I finished school in 1968 and worked in a bank and at different companies, and I was very happy. I remember in 1975, when I was working in the bank, a customer said he wanted to tell me that Vietnam was about to be taken over by the Communists. I was very skeptical and said, “How could this happen? How could we lose our country?” He told me, “I work in the U.S. Embassy, and I know that the Vietnamese are going to lose their country to the Communists. You have to leave if you don’t want to live under Communist rule. The Communists are about to win.” At that moment, I just couldn’t believe what he was saying. How could we be losing our country? Every day the bank is still lending money, conducting business. I didn’t believe him.

About a week later, I heard people talking, starting to say things like, “Chi, the Viet Cong are almost here; we have to leave the country. I have to go first. Bye bye, Chi.” Some people went by plane, some by other means – we didn’t pay attention. But in the end, it wasn’t until April 30th that we finally realized what was happening. My younger brother who was a pilot, he flew from Nha Trang to Saigon and told my husband and me, “Come with us. The Viet Cong are almost here. The U.S. has already signed an agreement to give up South Vietnam. They are not going to fight anymore.” He kept trying to convince us to leave the country, but my husband just yelled at him, asking him how he could leave his parents and his siblings and his country behind. My husband said he didn’t want to go, that he loved Vietnam too much to leave. Seeing that my husband wasn’t going to leave, his brother decided not to leave either, and he left his plane behind and returned home to Nha Trang to drive his wife and kids and his in-laws to Saigon. A week later, we lost our country; the Viet Cong took over South Vietnam. The old government had all left - they took planes or boats; they were all gone. After three days, South Vietnam was officially signed away to the Viet Cong. Everyone cried because we had lost our country.

Every day the newspapers reported about families who had fled by boat, which boats had capsized at sea. People slept at the airports trying to find a flight out of the country - it didn’t matter where, just out of Vietnam. I remember reports of people hanging off planes, dangling dangerously. People wanted to leave so badly that they hung off of these planes, but after awhile, most people had to drop down because the plane wouldn’t stop to let them get safely on, or they just couldn’t hang on long enough. There were a lot of scary scenes like this. What most people don’t understand though is why South Vietnamese are so afraid of the Communists. After the Communists took over, you would hear stories like how a poor couple who didn’t want to live under a Communist regime put poison into a big pot of porridge, killing their family of seven. I don’t know why so many people were this terrified; of course we were all so upset and sad, but we didn’t know what was going to happen. But some people were so scared that they poisoned their entire family. I don’t know if their fear was caused by rumors or something else.

Every day on the road, you would see the bodies of dead Viet Cong soldiers, probably killed by the South Vietnamese. You would also see the bodies of regular citizens, probably killed by the Viet Cong. Every day was like this. There was a lot of revenge killings from both sides all over Saigon, and the fighting lasted a long time. The South Vietnamese could just not get along with the Communists. I don’t know if it’s because of the way the Communists were - no education, no understanding, no love for mankind.

Anyone who was part of the South Vietnamese effort [former officers and soldiers, leaders, government officials, etc.] were sent to re-education camp. They were told that they would only be there for 10 days, but they weren’t released until decades later. Some died in the camps, some were able to return but their wives had remarried or fled the country or moved elsewhere, some were afraid to return home because they feared being rearrested. That is also a very tragic scene.

Those who didn’t flee by plane or boat, all they could do was stay. But it was difficult. Many had family members who were sent to re-education camp. How did they survive? It was hard. They didn’t know how to navigate the new society.

I worked at a bank. The Viet Cong seized the bank. They didn’t know anything about banking though so they would just come in like they were going to work and put their legs up on the table or slouch in a chair - they didn’t know what appropriate behavior or etiquette was. The soldiers assigned to the post at the bank didn’t have any money, or anything to make rice, so they broke down our fancy chairs and tables to use the legs as firewood to prepare their meals. They ate there, slept there, and worked there.

While many of my siblings had fled, I continued working for a few more years, but my heart was not in it. After that I quit, and I opened a small cafe and served the people in my neighborhood. For 17 years I worked and made enough to survive and be relatively happy. It helped that my sister, who was already in the U.S., sent up a couple hundred dollars every once in awhile, and we would split it up among our family members still in Vietnam.

My older sister had escaped by boat but was captured. We had to find ways to help them, to bring them food. Often times we were captured ourselves and imprisoned. Only after finding out that I worked in a bank did they let us go. My sister was eventually able to get out and started sponsoring family members out; some left early in 1987 and on, while others didn’t leave until after 10 or more years. My older brother successfully escaped by boat, but when he reached Kambuchea [Cambodia], he had to walk and then was captured and beaten. After paying money or gold, he was finally able to go to America.

During the 17 years I lived under the Communist regime, people said that if you had valuable possessions, you should bring them out on the street and sell them because under the new regime, we wouldn’t have money to spend. Everyone sat out on the street to sell their goods. With my brothers and sisters-in-law, we spread out a cloth and sold what we had: a sewing machine, a camera, jewelry. It was like this for a few years because there was no money - the government didn’t have money to give to its citizens, and we didn’t work; we only had our old money, and it wasn’t until a few years later that new currency was introduced and we had more stability.

When I stopped working at the bank and opened the cafe, there wasn’t a lot of business, and so I became an English teacher and worked out of my house. I put a sign out front and interested customers came in, most of whom had kids who they wanted to send overseas. For example, if a family had two or three kids who they wanted to send to America, they wanted their kids to speak English and so sent those kids to me. At the time, I had a lot of students - about 100 students. After a student would make it to America, they would write back to their family, saying, “Send another one of the kids to Co Tho because she teaches English very well - after a month of lessons, students can speak some English.” I taught them very basic phrases like, “What’s your name?”, “How old are you?”, “Where were you born?” The students were super happy because they could respond to these questions when they arrived in the U.S. That’s how word of the classes spread.

Luckily the Communists didn’t come and make it difficult for us. At the time, the government knew that they had to find a way to make sure the people could survive. They couldn’t harass or blame people for selling things on the street to survive, or harass a teacher for teaching English to survive. They probably realized that they had to allow people to find ways to make a living. Even after 10 years, the school was still up and running.

When I sold coffee during the daytime from my house, we didn’t have any problems, but my sister, who with her husband had a pharmacy in front of the house, ran into some trouble because of the “Pharmacy” sign still outside, even though they no longer were operating as one - they were selling fruit and dessert, but the police came by and told them to close up shop. When my sister tried to open shop again a few days later, the police came back; back and forth, back and forth. Ultimately my sister had to bribe the officers, arguing that she needed to work because otherwise she could not take care of her children. Afterward, she no longer had any trouble from them.

I taught English from around 1980 to 1990. During that time, some of my friends had become professors at a university run by the Communists, and they suggested that I teach there, too. I met with the Communist Dean of Politics and Business Administration and he gave me a job as a professor. I had a Master’s degree in Business Administration and so I could teach in the university. They didn’t actually check if I had the degree. I had also specialized in both Vietnamese and American Civilization, so I could teach either of those subjects. The school also paid a group of my friends to take these 600-700 page books and translate them from English to Vietnamese, and then make copies for the students to buy and study from. I taught at that university until 1992, when I came to the United States.

Can you tell me more about the work you do now - the jobs you have had and the positions you hold now? Also, can you talk about your advocacy work regarding human trafficking and domestic violence?

When I came in 1992, my kids and I enrolled in NOVA [Northern Virginia Community College system] and when I spoke English, no one could understand me! At the time, I could understand what the professors were saying, but they found it hard to know what I was saying. After five or six years, both of my daughters became pharmacists. For me, after I took a few classes at NOVA, I took the TOEFL test (Test of English as a Foreign Language], and thanks to the 11 years as an English teacher, I had no trouble on the grammar and listening sections, but a little bit on the writing and speaking sections. On the first test I took, I got 553 points, which was more than the score of 500 I needed to get into college. I then signed up for accounting classes but after only one or two months, I got a call from Arlington County. I had been working at a printing house for about six months, and learning computer skills at the Arlington Career Center, and with the new skills and my good English, I got a job at a law firm.

After a year at the law firm, I got a job at LT Services, a financial services group. it provided me with health insurance. Because of my experience, I later got a job as an Accounting Assistant at the Arlington County, where I worked for nine years until the recession when I was laid off with 30 other people. A month after this, I got a job at BPSOS [Boat People S.O.S.], and I have been working here for the last nine years as a case manager for human trafficking and domestic violence. A lot of different lawyers and case managers interviewed me, and after several rounds, I began working immediately. I didn’t have any prior knowledge of these fields, but they, Maryland and Fairfax County, trained me well. I worked in Maryland for about three years, until 2010, when I asked to be transferred to the Virginia branch closer to home because I heard there was an opening. I have been here ever since.

I have been to many intensive training sessions, including at places like the University of Richmond where I took a domestic violence advocacy course. One hundred and one people applied to take the course but only 20 people got selected, including myself. This program allowed me to get licensed and receive certification to handle domestic violence cases. In terms of human trafficking, well-known experts in the field and various organizations helped to train me. In my work, I help people get financial assistance, apply for food stamps, find housing and jobs, and search for mental and medical services. But I also know how to recognize victims and to find ways to get people help as quickly as possible.

During my time at BPSOS, I remember one year when the government didn’t have enough money to fund BPSOS and we didn’t have enough lawyers or caseworkers. In 2010, there was only one case manager, me, and one lawyer. We received two grants that year, which required us to serve at least 50 individuals, and so the two of us had to work extremely hard. The following year however, because we couldn’t reach our target the year before, we lost one grant. We were both very passionate though and we worked incredibly hard, doing the work of about three people but doing so happily. I even found time to start a Buddhism program to broadcast Buddhist radio and organize annual pilgrimages to local temples in Maryland; Washington, DC; and Virginia. I had to take a break from all this organizing though because I have been busy preparing for the arrival of another grandchild around New Year’s [2017].

When I first came to the United States, I cried so much for the first three years, particularly because I missed Vietnam, my home, my friends, my mom. My mother, who was sponsored over, didn’t like living in the U.S. because she didn’t speak English and had a hard time adjusting, and so she went back to Vietnam. I went back to visit her after three years for her 80th birthday, and returned again when she got sick. After she passed, I finally got used to life in the States. My whole family is here, there is a big Vietnamese community, and I feel safe and protected by the government here. Though I lament the loss of my country, I am so happy to be an American citizen. I can send money back to Vietnam and help my friends and family, build schools, donate to Vietnamese charities to help those in need, and many other ways. I can also help to make a difference here, like volunteer work in DC to feed the homeless, and my work here at BPSOS, being a source for people to get housing, learn how to drive, and find jobs. Life isn’t just about money but about finding meaning.

One of my younger siblings has a restaurant at the Eden Center [the Vietnamese center in Falls Church, Virginia], and every time she needs extra hands, she asks me if I know of people who need a job. One of her children has a salon and also finds help this way. The Vietnamese community is a very open network, with people always trying to help one another. For example, through this network, I met you, Tammy, and found out about Project Yellow Dress. Now hopefully you can meet more and more people!

The Vietnamese community does so much, helping people here and abroad. Using our hands and our compassion, our hearts are very open, and this work makes me so happy. We don’t know when the day will come that we can no longer give, so we do as much as we can until we can’t go on anymore. I’m 72 years old, but I like to be out in the world, meeting people, helping people.

What do you want people to learn from your story, your experience? What are the lessons or messages you want to share with others?

Since I was little, I was really passionate about community service, about helping the world. Before I began work at Arlington County, I had already been teaching English to low-income community members. Later I taught Vietnamese to little kids. Through all my jobs, I have been able to help so many people in so many different ways. When I was in Vietnam, I thought that when I got to America, I would just worry about myself and my family, but through fate and destiny, I have had the opportunity and the good health to be able to help others. The majority of the Vietnamese community is no longer the first generation immigrants, but rather the group of second generation Vietnamese Americans. I am so grateful to see how America, our second home, has embraced not only its own people, but people of all backgrounds around the world. I have been able to start a new life here, and am inspired by how it has taught me so much about friendliness, charity, and compassion.